It started as a mild ache on the outside of my kneecap during a routine run. I shrugged it off as “just one of those runner pains” and kept pushing. A week later, I was limping home, knee throbbing. That’s when I realised: I had the dreaded Runner’s Knee. Little did I know this would kick off a journey of frustration, learning, and ultimately recovery. In today’s blog, I want to talk about something I’ve personally experienced, that dull, frustrating ache around the front of the knee that creeps in after runs: Runner’s Knee, also known as Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome (PFPS).

For me, it started when I caught that runner’s high and ramped up my training volume too quickly, extra runs in the week, longer sessions, and not enough recovery. Within a few weeks, that mild ache turned into a sharp, consistent pain every time I went downstairs or stood up after sitting for too long.

If this sounds familiar, you’re not alone. Runner’s knee is one of the most common injuries I see in both new and experienced runners. Let’s break down what it really is, why it happens, and how you can overcome it, with a bit of evidence, experience, and a story or two from my own recovery journey.

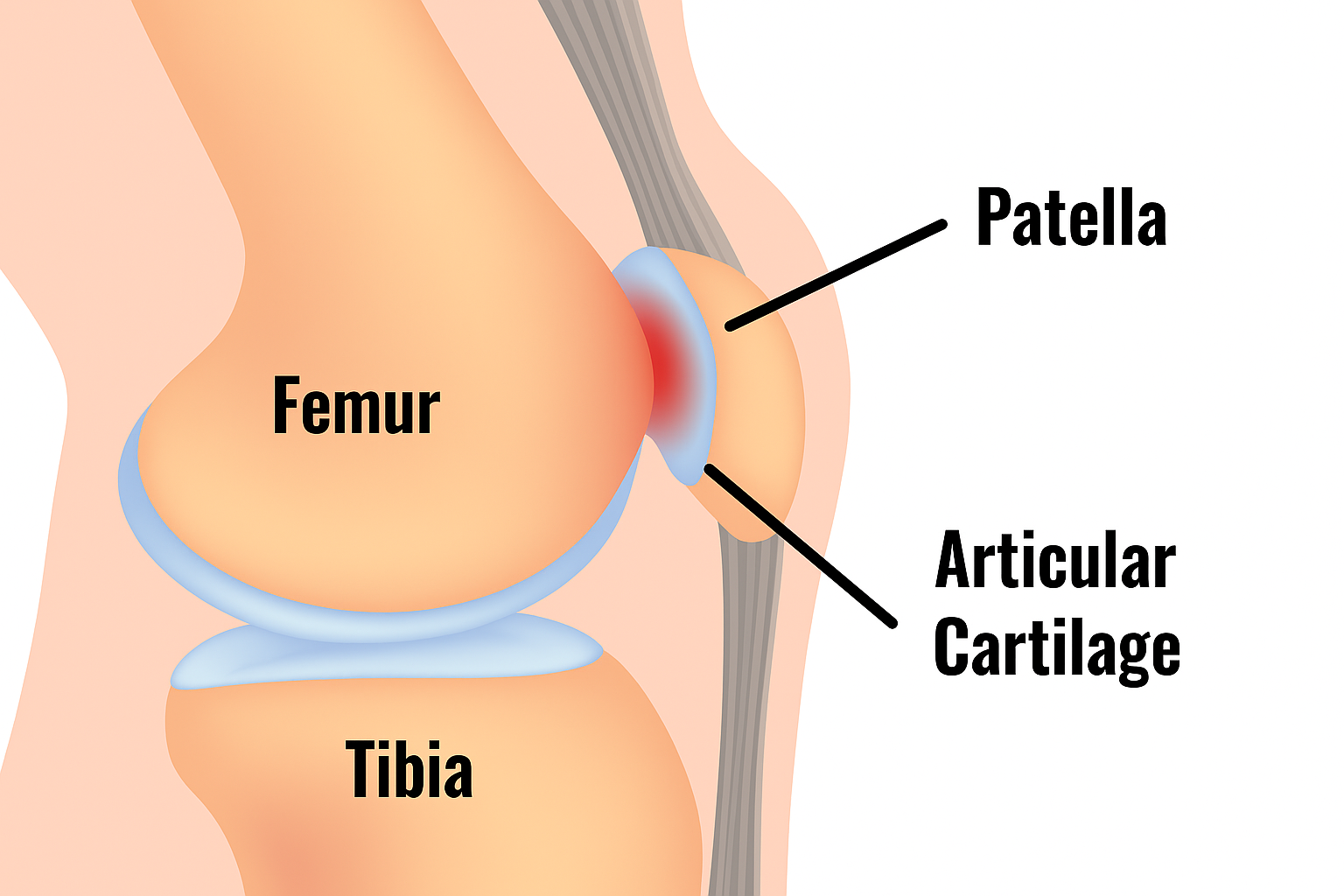

“Runner’s knee” is actually a pretty spot-on nickname. Clinically, Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome (PFPS) is defined as pain arising from the patellofemoral joint; the area where the patella meets the femur, and is aggravated by activities that increase pressure on the joint, such as squatting, running, or prolonged sitting (Crossley et al., 2016), – which is just a fancy way to say “your kneecap area hurts when you load the knee, but there’s no obvious structural damage like a tear.” PFPS often lacks a specific, identifiable structural lesion like a ligament tear or muscle strain. Instead, the pain is caused by the irritation and inflammation of the soft tissues surrounding the kneecap, triggered by improper mechanics and increased stress over time (Lankhorst et al., 2013).

Runner’s knee is incredibly common, not just for marathoners, but for everyday runners and even non-runners. PFPS is one of the most prevalent causes of knee pain in physically active adults, affecting an estimated 15–45 % of people at some point (Smith et al., 2018). Among runners, it’s practically an epidemic, accounting for roughly 19–30 % of all injuries in women and 13–24 % in men (Esculier et al., 2016). No wonder they call it runner’s knee!

The good news (if you can call it that) is that runner’s knee is usually an “overuse” injury rather than an acute traumatic one. That means it creeps up due to irritation from repetitive stress. In my case, there was just an ache that got worse. Still, when you’re in pain, it sure feels like a big deal. And while it can feel stubborn, with the right approach, it’s very treatable.

Runner’s knee often starts as a dull ache around or behind the kneecap and may progress to sharper pain if ignored. Common symptoms include:

If left untreated, symptoms can persist for months and may affect everyday activities, so early management is key.

Let me confess: I made just about every classic mistake that can lead to runner’s knee. In hindsight, it’s almost like I followed a recipe for PFPS.

It started with excitement and a lack of patience; I increased my weekly mileage and intensity without enough rest or strength work – a classic case of “too much, too soon”. Research shows that rapid spikes in training load are a major cause of PFPS, as they exceed the tissue’s capacity to adapt (Esculier et al., 2016). Add in running on hills or hard surfaces and… Cue the knee pain. In many cases of runner’s knee, you find the person (hi, that’s me) recently changed something in their routine – more mileage, faster runs, or new terrain, and the knee simply couldn’t adapt fast enough.

I ignored the early twinges. When my knee first started acting up, I did what a lot of runners do: pretended it was fine. I popped a couple ibuprofen, iced it a bit, and tightened my laces thinking maybe my shoes were loose. Spoiler: that didn’t fix it. Pain is our body’s alarm system, and I effectively hit the snooze button over and over. Looking back, I realise I was training through pain out of fear of losing fitness. But ignoring that initial discomfort only invited it to become a full-blown, ongoing issue.

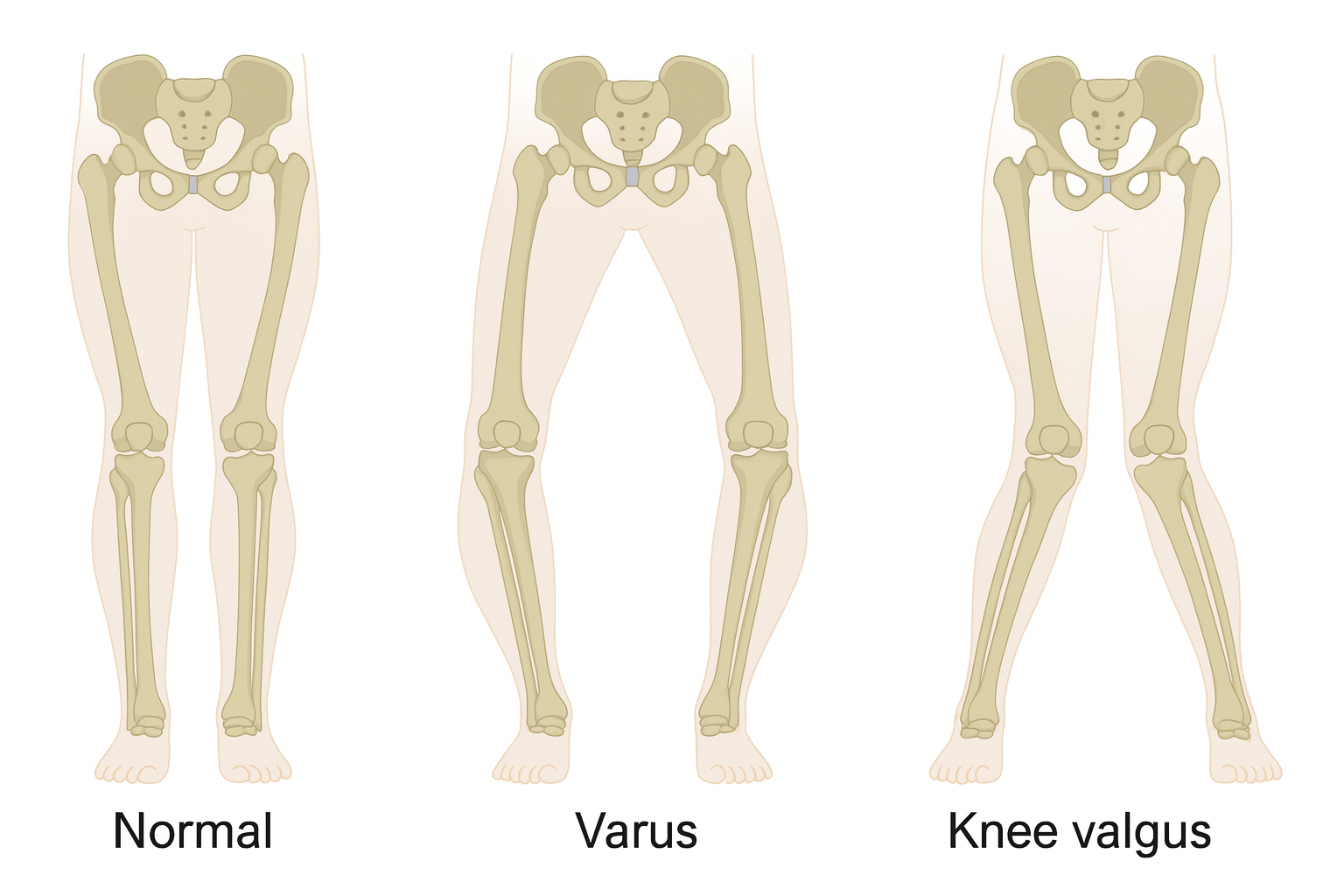

Poor biomechanics played a role. Once I finally paused to dig into the research, I learned a few movement issues were contributing to my runner’s knee. For one, my single-leg squat showed my knee caving inward (knee valgus), and I struggled to do clamshells. This indicated poor neuromuscular control of the hip and knee from weakness in the gluteus medius, external rotators and knee extensors (quadriceps). I later found that Patients with PFPS often show reduced quadriceps and hip external rotator strength compared to healthy controls (Papadopoulos et al., 2012; Bisi-Balogun et al., 2015). As proven by Rathleff et al. (2014), this can lead to poor knee tracking and increased stress under the kneecap. Basically, my alignment wasn’t ideal; each stride was giving my kneecap a bit of a beating due to how my legs were moving.

However, here’s an interesting twist I discovered: weakness might be as much a result as a cause. In two studies that followed new runners over time, those who eventually developed runner’s knee did not start out with weaker legs, they were just as strong as other runners before the pain (Esculier et al., 2016). It’s likely that once the knee began hurting, pain inhibited the muscles, and then they got weaker. In other words, my painful knee could be causing certain muscles to shut down, creating a vicious cycle.

The result: a perfect storm. My case was basically a mix of classic PFPS triggers. Here’s what summed it all up, and what often causes it for others too:

Once I accepted that I indeed had runner’s knee (stage 1: denial complete), I shifted into problem-solving mode. I’m not going to lie, the recovery tested my patience. There were weeks of boring exercises, FOMO as I skipped group runs, and constant temptation to “test” the knee. But step by step, I made progress. Here’s what my recovery journey looked like, along with the science behind each step:

I learned quickly that total rest wasn’t the answer. The goal was relative rest, reducing painful activities but keeping the body moving. Evidence supports staying active within pain limits, as it promotes circulation and prevents deconditioning (Collins et al., 2018). So, I hesitantly took a break from running for a couple of weeks and focused on other activities that didn’t hurt, like upper-body workouts and gentle cycling, to stay sane. Crucially, I didn’t stop moving altogether.

Whilst resting, I did what I do best at Kinetix Rehab, I ran myself through the same process, assessing flexibility, strength, gait, and training habits. My assessment revealed weak glutes, tight quads, and some hip instability, pretty typical findings for PFPS. My rehab plan focused on progressive strengthening of the hips and thighs.

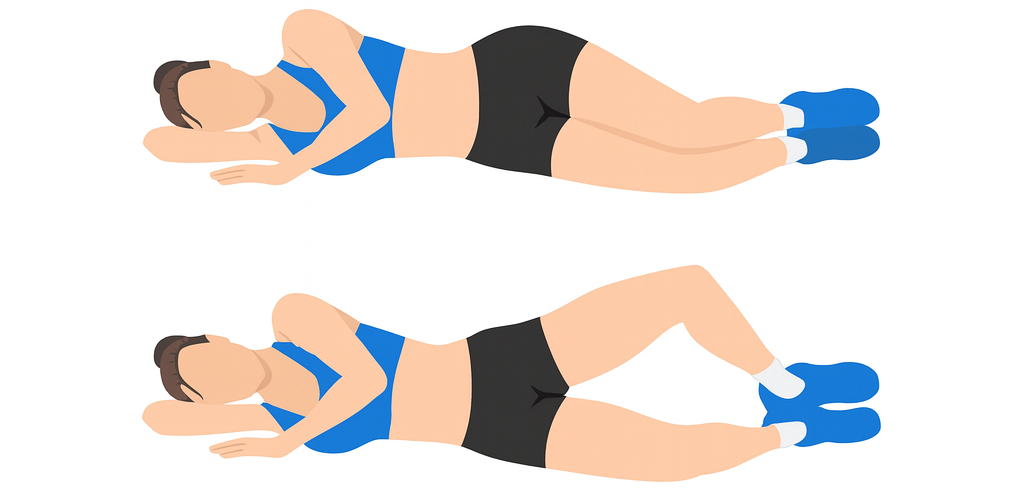

Weak glutes (especially glute med/max)

These muscles help control hip and knee alignment. Weakness here can cause the knee to drift inward (valgus).

Key exercises:

Tight quadriceps

Tight quads can increase compressive forces under the kneecap.

Key exercises:

Hip instability / poor control

Lack of stability at the hip often leads to inefficient knee tracking.

Key exercises:

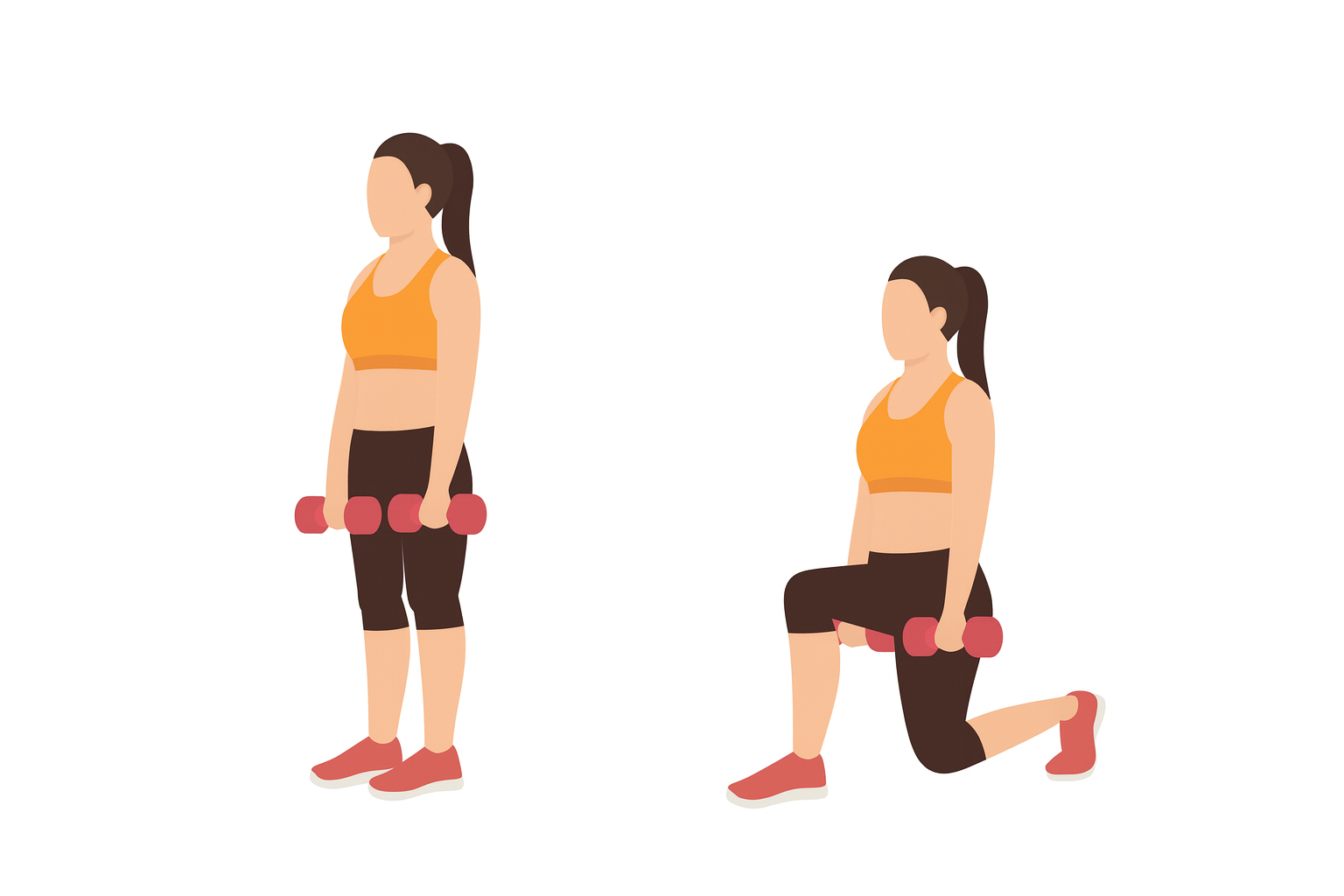

General knee and thigh strength

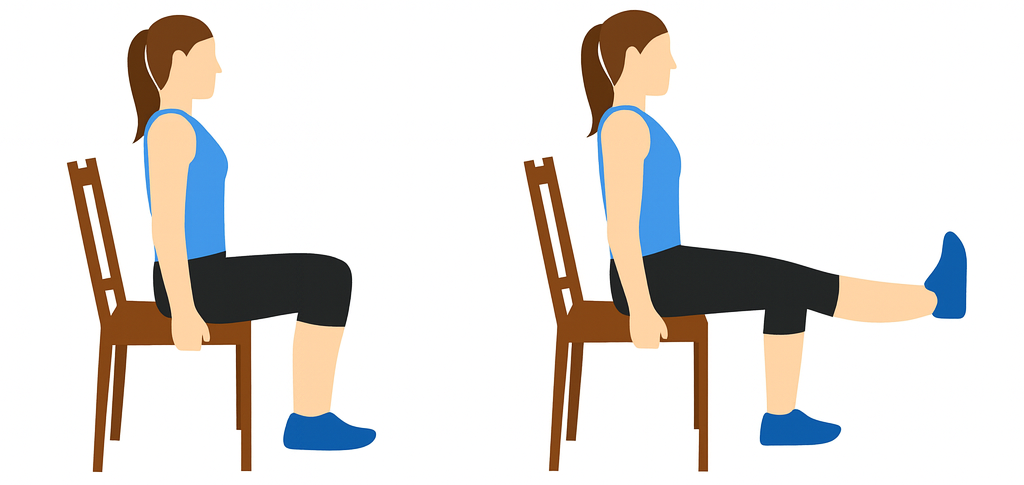

Strengthening the quads, particularly the vastus medialis oblique (VMO), helps support and guide the patella during movement.

Key exercises:

The key was gradual progression and staying within a pain-free range. I stuck with this strength routine diligently. It became almost like a second job (unpaid, unfortunately!). I threw myself into the program that Kinetix (myself) provided. Sure enough, within about 4 weeks I began noticing real improvements: my knee was aching less during daily activities, and I could do harder exercises with less pain. By 8 weeks in, I was virtually pain-free doing normal things and had started easing back into short runs. A large body of research backs this up. Multiple randomised trials show that combining hip and knee strengthening provides the best outcomes for pain reduction and long-term function (Barton et al., 2018; Rathleff et al., 2014). The current clinical consensus is that exercise therapy is the cornerstone of PFPS management (Collins et al., 2018).

Once the pain had settled, I worked on improving my running form. I started by grabbing my phone and filming myself running on a treadmill. After an analysis, the video showed I was over-striding and landing heavily on my heels, both of which increase knee loading.

I introduced gait retraining, increasing my step rate slightly (cadence) and focusing on landing with my feet closer to my body. Research by de Souza Jr. et al. (2024) found that a short, two-week gait retraining programme significantly reduced knee pain in runners with PFPS and improved function at six-month follow-up. That meant shorter, quicker steps (which naturally reduced the impact on my heel). It felt odd at first, like I was doing a quick pitter-patter, but I gradually got used to it, my running felt smoother, and my knees noticeably happier.

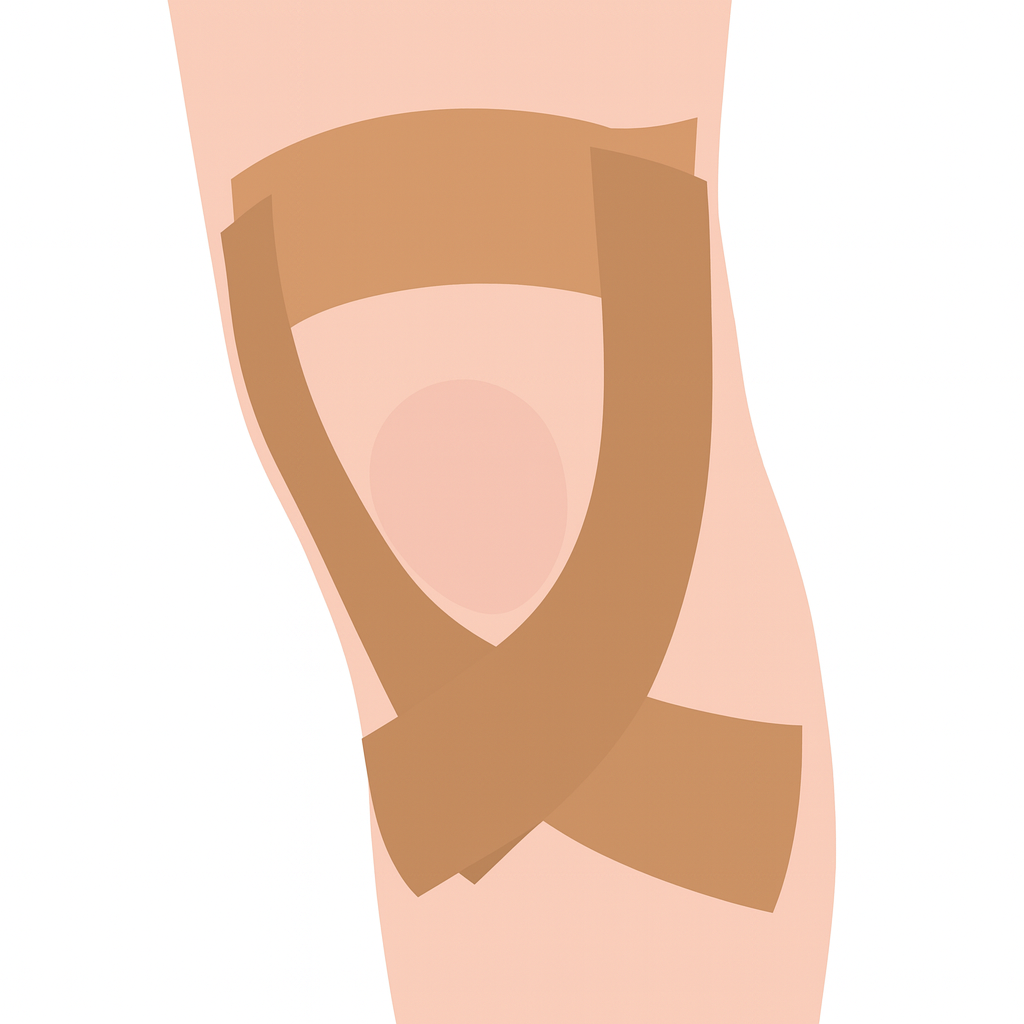

During early rehab, I used patellar taping and foot orthoses to manage symptoms. Patellar taping can temporarily relieve pain by improving kneecap alignment (Callaghan & Selfe, 2012), while arch supports or orthotics may help redistribute forces through the lower limb in the short term (Barton et al., 2018). In my experience, that’s exactly what it did. These tools shouldn’t replace exercise, but can be great adjuncts when pain is limiting progress.

After weeks of consistent rehab, I started re-introducing running through walk-run intervals and staying on flat, soft surfaces. For example, jog 2 minutes, walk 1 minute, for maybe 20 minutes total. When that felt okay, I slowly increased the running portions. I continued my strengthening routine alongside it, something I still do to this day. Looking back, it was clear that my big mileage jump and sudden hill sessions were the main culprits. I’d ignored the golden “10% rule,” which advises increasing mileage or intensity by no more than about 10% per week. Once I respected that principle and rebuilt gradually, my knee tolerated load far better, and my running started to feel smooth again.

A big lesson I learned is that these rehab exercises are not just for recovering, they’re for preventing. Prevention often comes down to smart training and consistency. I’ve basically turned them into a “prehab” routine. By keeping my quads, hips, and core strong, I drastically lower the chance of runner’s knee making a comeback. Based on both my experience and the research, here are key habits that make all the difference:

Studies show that continued exercise and load management can significantly reduce recurrence and improve long-term outcomes (Rathleff et al., 2016).

Today, I’m back to running pain-free, and honestly, I’m grateful for the whole runner’s knee saga; it forced me to train smarter. I now make strength work, proper warm-ups, and gradual progression a non-negotiable part of my routine.

That experience sparked something bigger. At Kinetix Rehab, I now work with runners dealing with injuries like PFPS, using the same evidence-based approach. Every plan starts with a detailed assessment, looking beyond the knee to identify movement patterns, muscle imbalances, and training errors. From there, I combine hands-on treatment such as sports massage and manual therapy with progressive strengthening and load management, tailored to your specific goals.

Not local to me? Fear not, I’m excited to announce that I’m developing online exercise programs, complete with step-by-step video routines you can follow from anywhere. These programmes are built around the same rehab strategies that helped me recover. Consider it a virtual coach in your living room, keeping you on track. I genuinely can’t wait to share them with you!

If you’re currently struggling with knee pain or noticing early signs of discomfort, visit www.kinetixrehab.co.uk or contact me directly at Jack@kinetixrehab.co.uk. Together, we’ll build a plan that gets you back to running stronger and staying that way. Because if there’s one thing this journey taught me, it’s that recovery isn’t just about getting rid of pain, it’s about coming back smarter, stronger, and more resilient than before. Yeah, sounds like something you’d read on a gym wall… but it’s true.

Contact for a free online consultation...

5 Responses

It’s fascinating how online platforms like bigwin casino app download apk are adapting to local preferences – GCash & PayMaya integration is smart! Responsible gaming is key, though; easy access needs safeguards. A streamlined signup (2-3 mins!) is a definite plus.

It’s great to see platforms like BW777 prioritizing tech and user experience – predictive analytics sound fascinating! Responsible gaming needs innovation too. Check out a bw777 game for a modern take on entertainment, but always play within your limits! 😊

Roulette’s seemingly random nature hides fascinating probability! Understanding the house edge is key. Platforms like jiliko app emphasize secure play & responsible gaming-important for any strategy, honestly. KYC procedures are a good sign too!

Хорошим вариантом для SEO-специалистов является база профилей для хрумера, содержащая активные ресурсы.

Регулярное обновление данных возможно через скачать свежие базы xrumer https://www.olx.ua/d/uk/obyavlenie/progon-hrumerom-dr-50-po-ahrefs-uvelichu-reyting-domena-IDXnHrG.html, что повысит эффективность продвижения.